The Ball’s Rolling

Published:

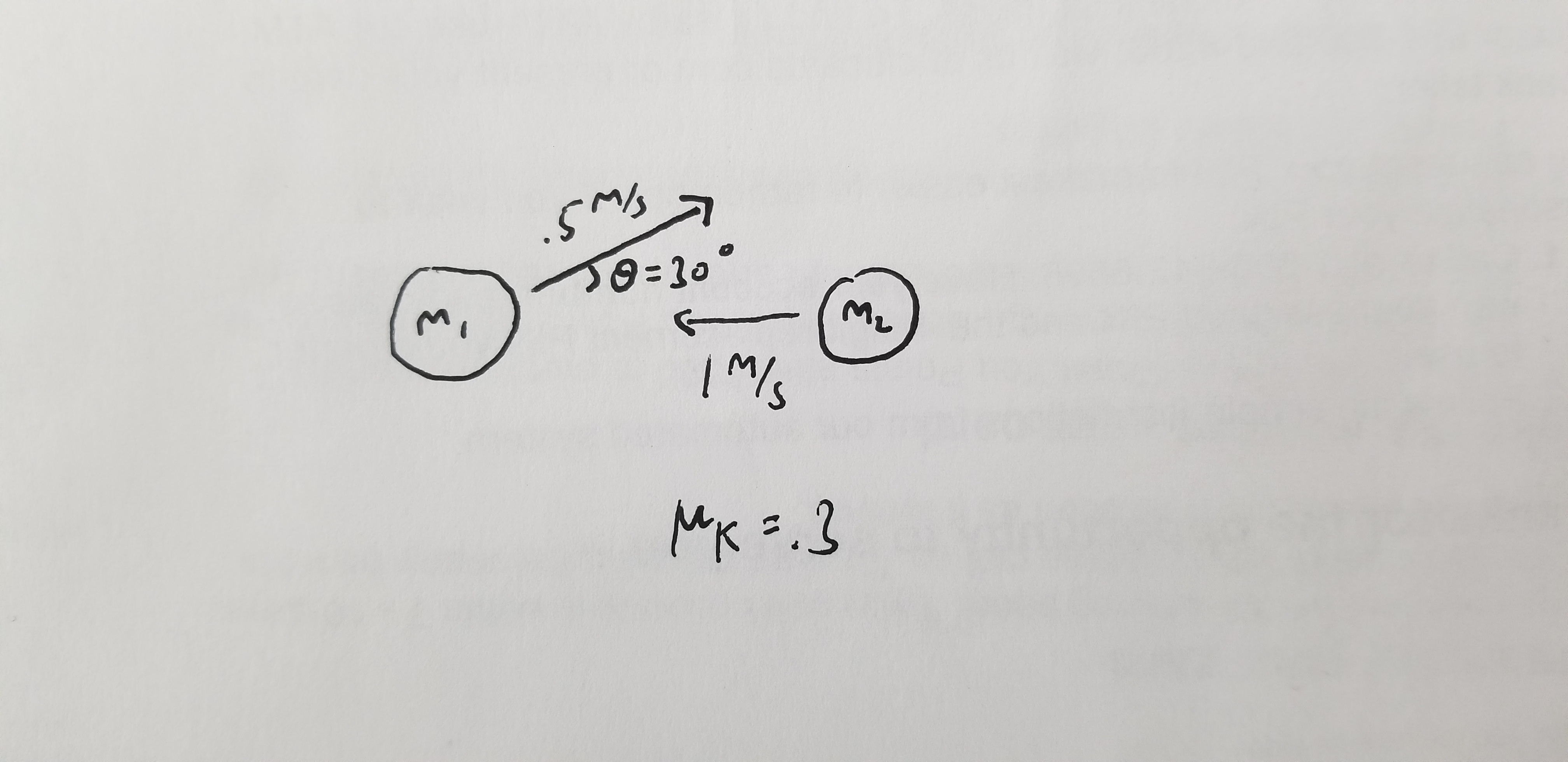

Let’s peruse a quick lesson in freshman mechanics. If you know the masses and velocities of two pool balls about to hit each other, you’ll be able to figure out which directions and what speeds they both go. Conservation of momentum.

With a few more variables in hand, you could figure out how long it would take those balls to stop due to friction and what velocities they’d be at n seconds after they collide.

Simple enough, yeah?

Well, in 1814, physicist-philosopher Pierre-Simon Laplace thought he’d make things a little more interesting.

He wanted to expand how we think about the determinate aspect of physical systems to the whole freaking universe.

Leave it to the physicists to make things fun.

Section 1: Physical Determinism

The thought experiment he proposed, in a nutshell, was this:

Imagine there’s an omnipotent cat named Garfield (1), that knows the exact position and momentum of every particle in the cosmos. Based on classical mechanics, Garfield should be able to calculate and predict every interaction between particles in the universe. He could then extrapolate that to larger systems and predict every action in the universe.

The philosophical upshot of this theoretical entity is best said by Laplace:

“Nous devons donc envisager l’état présent de l’universe comme l’effet de son état antérieur, et comme la cause de celui qui va suivre

We may regard the present state of the universe as the effect of its past and the cause of its future.”

Effectively, according to Laplace, the universe is completely pre-determined from its initial conditions. Once the ball gets set in motion, the fate of the universe is theoretically predictable and sealed.

In essence, Laplace is reducing our universe, from heavenly bodies to H. pylori, to the physics problem where the billiard balls hit each other.

The most obvious arguments against this are those of statistical and quantum mechanics. By definition, systems where these models apply have a degree of indeterminacy. For example, Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle clearly states that it is absolutely impossible to know the absolute position and momentum of a given particle.

It is important to note, however, that the principle states that it is impossible to know the absolute position and momentum of a given particle. This does not mean that the absolute position and momentum of a given particle do not exist.

Einstein famously stated that God does not play dice. This is the hidden variable response to quantum arguments against Laplace’s demon. An other-dimensional being may have extra variables which would permit them to understand and know every aspect of all particles, including subatomic particles. A being in this other universe may even have the computational power to understand and run a model of our whole universe. (Did somebody say “The universe is a simulation” blog post?)

If we presuppose a theoretical entity that could have all this information regarding the universe, the moral of Laplace’s experiment holds true. The ball of our destinies rolls determinately. The other-dimensional being might be laughing at how ironic it is that I’m writing this blog post completely out of my own accord.

In the end, it turns out that to individuals made of particles from this universe, a set which I happen to be a part of, it is unlikely that we’d ever be able to reach this level of prognostication.

At least we don’t have to worry about physical determinism now. In this universe.

But why have so many physicists fervently and fastidiously tried to disprove Laplace (2, 3, 4)?

Section 2: Biological Determinism

Likely, it’s because his thinking leads us to a pretty seminal question in philosophy, physics, cognitive science, and biology. Do we have free will?

Laplace’s demon prompts this line of inquiry because if our actions are completely predictable and set in stone from before Day 0, how can we really say we have any internal locus of control?

The immediate, intuitive reaction to any affront to our free will is “Of course I have autonomy.” If we want, most of us can grab a glass of water without issue and lift our hands up to drink it.

Laplace surely can’t make an argument regarding human lives: we aren’t solely collisions of masses (unless it’s 3 am at Rocco’s), so how can we pretend that that’s all our lives are?

This is where behavioral neuroscience comes in.

Do we have control over why we lift up our hands?

Obviously, it’s because we’re thirsty. Free will, right?

Again: Why do we lift our hands in the first place?

Likely, it’s because the osmoreceptors and the renin-angiotensin system signals to our brains that we need water. We have less control over ourselves than the millions of years of evolution which led to our complex homeostatic systems. Evolution controls our actions. In general, we are guided by sex, hunger, thirst, or other physiological factors.

Even actions of self-actualization may have evolutionary roots.

In fact, there’s a really interesting set of papers saying our minds are fooling ourselves into believing we have free will (5). Through a set of experiments, psychologists find that the belief that our actions are due to personal autonomy is because, after every action we perform, we label what we’re doing and then assign a logical reason for it. It is quite possible that our brains are retroactively giving reasons for actions that are out of our control. To me, this phenomena is eerily similar to how split-brain patients justify what each half of their body is doing (6).

Ultimately, physical determinism is impossible to comprehend as a being from this universe. I’m unsure on where I stand regarding it. Nonetheless, I don’t think we have free will. Likely, we’re containers of biochemicals who do as the neurotransmitters sending signals across our neurons tell us to. Natural selection has selected for us to do things that help us propagate our genes. Sure, we have sex, eat food, and hang out with friends because we enjoy these actions. But millions of years of evolution outside of our control are why we enjoy them.

Of course, the question of whether or not it’s useful to think of ourselves as beings without free will… That’s another blog post altogether.

Citations

1) https://www.reddit.com/r/imsorryjon

Okay, he didn’t say Garfield. Maybe he said demon. Same thing.

2) Wolpert, D (2008). https://arxiv.org/abs/0708.1362t.

3) Binder, P (2008). http://www.astro.uhh.hawaii.edu/documents/Binder_nv-toae.pdf.

4) Sommer, C (2013). https://arxiv.org/abs/1303.2719.

5) https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/mind-guest-blog/what-neuroscience-says-about-free-will/

6) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wfYbgdo8e-8. Highly recommended video+YouTuber.